But the 33-year-old Rees’ dream for the sculpture is much larger: She’d like to see it turned into a life-size piece. That’s also the hope of the Marine Raider Foundation. The work is designed to be viewed as a large scale piece, Rees said. She sculpted it from the viewpoint of looking up at the Raiders faces, and she used live models to sculpt the piece.

Before it reaches Virginia, it will have a few special stops. After Tacoma, the piece will be presented at the Marine Raiders reunion in San Diego, California. Then, it will travel to Rees’ alma mater, Laguna College of Art and Design, in Laguna Beach, California.

The 37-inch high by 57-inch wide bronze sculpture, which Rees estimates is close to 400 pounds, is a snapshot of a night in November 1943, as Marine Raiders infiltrated Bougainville Island’s harsh jungle landscape.

Rees chose the figures carefully and worked closely with a curator at the Marine Corps museum as well as military collectors across the United States. It was crucial to get the right details and the right characters.

Up front there is a Marine Raider, armed to the hilt, carrying a Browning Automatic Rifle, or BAR. Behind him stalks a war dog and handler. Bringing up the rear, crouched low and speaking into a radio is a Navajo Code Talker.

For the BAR man and the war dog handler, Rees used former Marines dressed in WWII combat gear. The men had served two tours in Iraq.

Rees used a German Shepard as a live model for the piece.

“His name is Finn,” she joked in her speech at the unveiling. “And I have a pound of his hair in my studio.”

The Navajo Code Talker model is a member of the Navajo nation who talked and sang in his native language while she worked.

It was the Navajo language that provided a key tool for the Marine Raiders. Navajo Code Talkers developed a military code based around their native tongue. It allowed Code Talkers to communicate back and forth. The Japanese never cracked the code.

Before designing, Rees scoured books showing WWII memorials, the most famous being the flag raising at Iwo Jima. She expanded her search to include all war memorials.

“I always look to the greats for influence as far as what I see as beautiful and meaningful,” she said.

The inspiration, sculpturewise, comes from a life-size memorial. The sculpture of Gen. Robert Gould Shaw marching off to war located in downtown Boston. Rees said its always been a favorite of hers. Artist Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ piece depicts Shaw leaving Boston to fight in the Civil War with an infantry that brought together white soldiers and African-Americans as brothers in arms. Rees said the style of the piece informed her latest work. Rees found the use of a relief background effective in Saint-Gaudens’ sculpture.

“It totally gives you a sense of place that is hard to do through sculpture,” Rees said.

In “Souls,” the relief background sets a jungle scene, but there’s a nuance many viewers may miss, she said. She’s etched the silhouettes of fellow soldiers in between the trees, adding an “eeriness” to the sculpture. The relief is meant to bring home “the insanity of fighting in a jungle environment,” she said.

Rees herself has always been an artist.

When she went to the Laguna College of Art and Design, she was required to take a sculpture class. She got hooked.

“From then on, I was found in the sculpture department at all hours,” she said.

Born and raised in Gig Harbor, Rees said she began to blossom as an artist when her family moved to Ecuador for three years. She completed high school there and spent time painting murals and portraits of the local people.

She graduated with honors from Laguna in 2003. She lives and works in Gig Harbor and is best known in the area for the sculpture outside St. Antony Hospital.

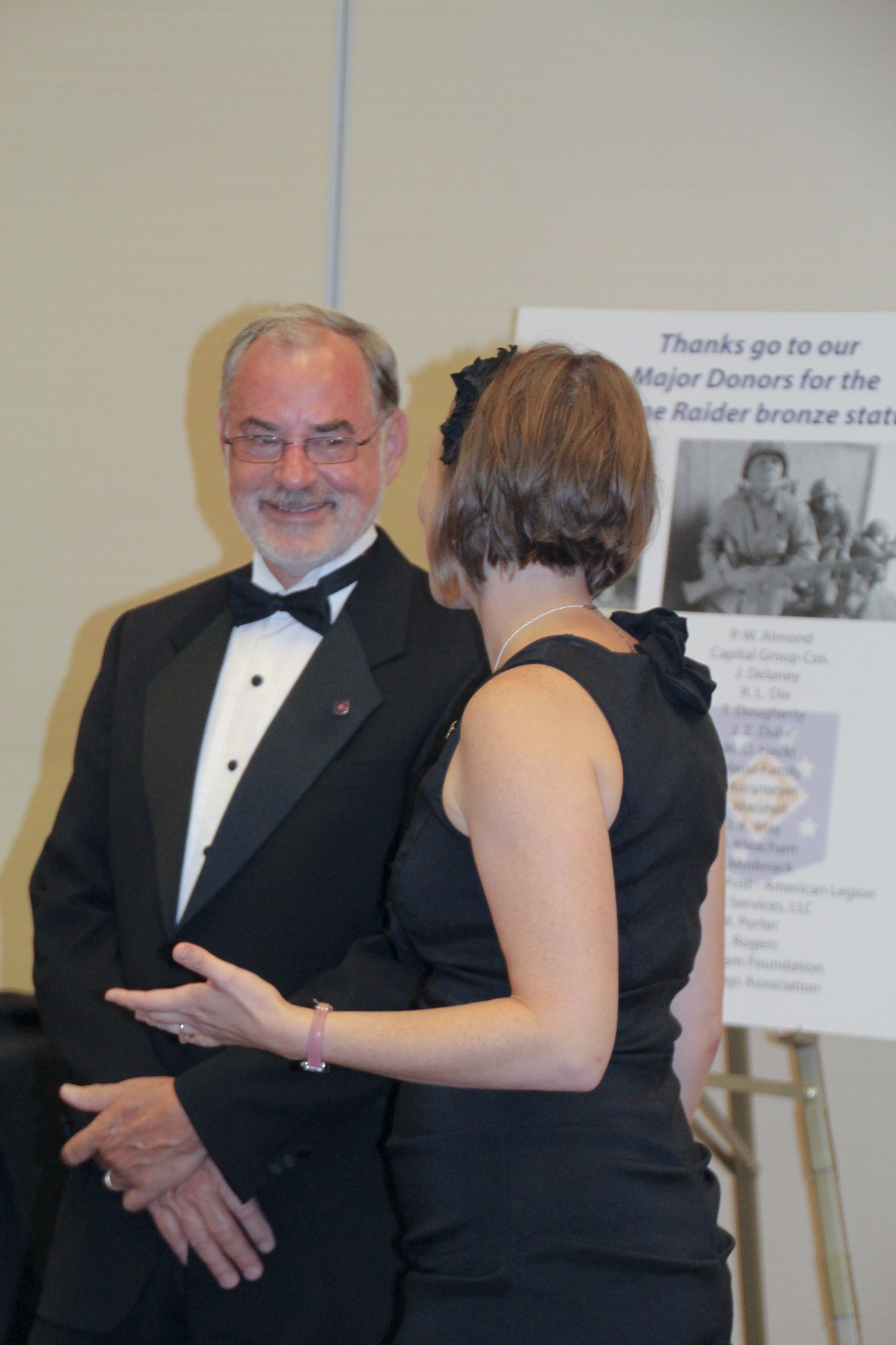

Rees is excited to accompany the sculpture on its tour. She is excited to see soldiers and veterans react, especially Marines.

“(The Raiders are) really the grandfathers of reconnaissance Marines and MARSOC,” Rees said.

Article by Karen Miller: 253-358-4155 karen.miller@gateline.com Twitter: @Gateway_Karen